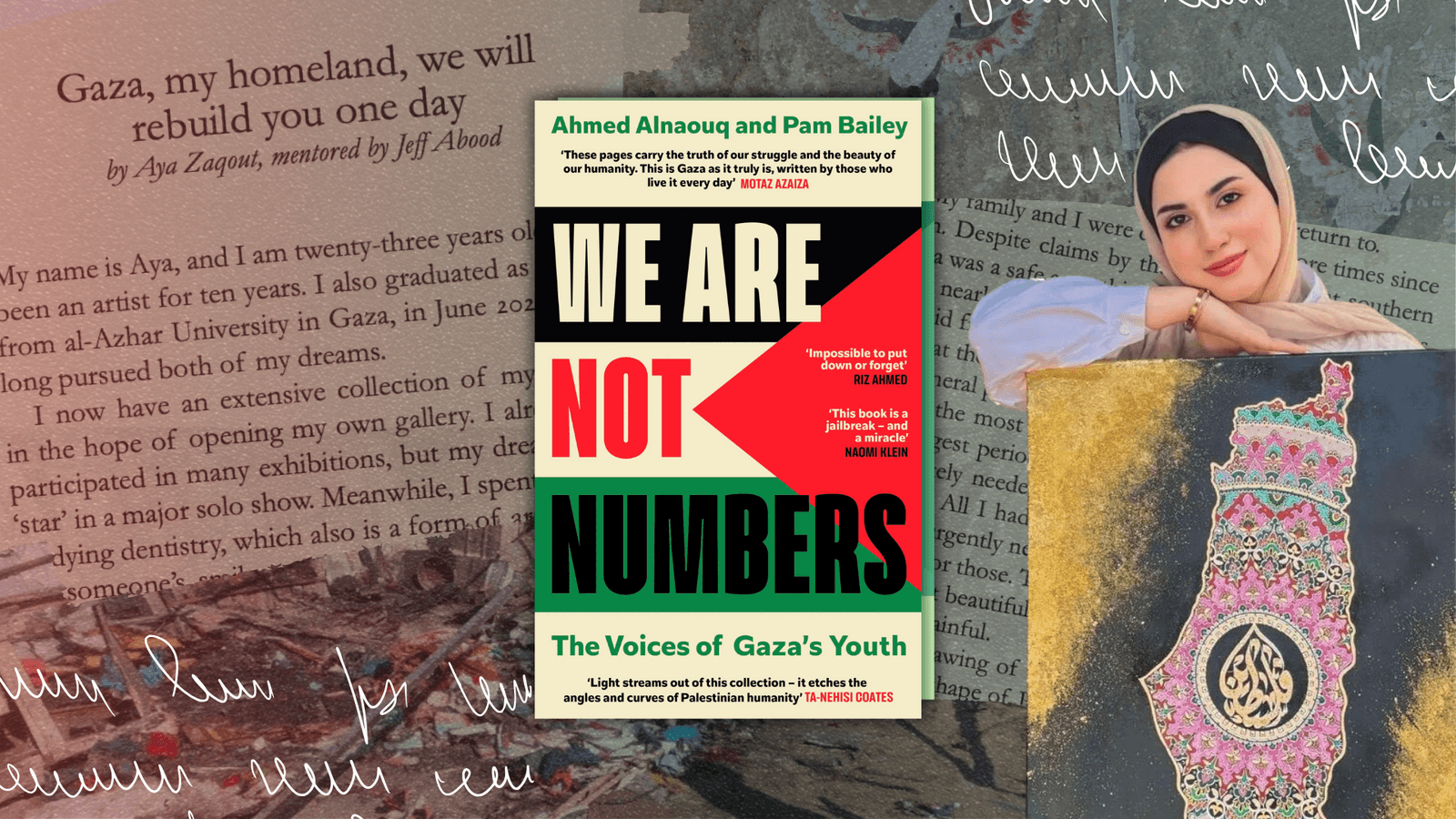

We Are Not Numbers: The Voices of Gaza’s Youth by Ahmed Alnaouq and Pam Bailey is a powerful new collection of writing by young people living in Gaza – but its concept began back in 2014, when co-founders Ahmed and Pam were first brought together. That summer, Ahmed’s 23-year-old brother Ayman was killed during the Israeli military attack on Gaza. In the depths of depression, Ahmed met Pam, an American journalist living and working in the Gaza strip, who encouraged him to honour his brother through writing. Together, they shaped his words, and through that exchange Ahmed – now a journalist and human rights activist – began to heal.

From this, We Are Not Numbers was born: an initiative pairing young Palestinian writers with mentors from around the world to help develop and refine their narrative, much like Pam supported Ahmed, with their stories shared on the WANN website. Now, some of these experiences have been collated into a book shining a light on the realities, emotions and everyday worlds of both those living in Gaza, and those who have found a way to leave.

Below is a chapter by Aya Zaqout, a young artist who shares her experience of displacement, being separated from her family and a yearning for the home she once knew.

Gaza, my homeland, we will rebuild you one day by Aya Zaqout, mentored by Jeff Abood

My name is Aya, and I am twenty-three years old. I have been an artist for ten years. I also graduated as a dentist from al-Azhar University in Gaza, in June 2023. I have long pursued both of my dreams.

I now have an extensive collection of my artwork, in the hope of opening my own gallery. I already have participated in many exhibitions, but my dream was to ‘star’ in a major solo show. Meanwhile, I spent five years studying dentistry, which also is a form of art. Enhancing someone’s smile, and thus making a difference in their life, has been incredibly fulfilling for me.

However, the war on Gaza has drastically altered those plans.

On 7 October, just two months into my year-long, postgraduate dental training, the Israeli occupation forces forced me to evacuate my home in northern Gaza and flee on foot to the south. Along the way, we were forced to pass through many army checkpoints. Israeli soldiers stood in a line along the path we walked, calling out names on microphones. They forced us to raise a white flag and show our IDs. They randomly selected young men and ordered them to strip off their clothes. I saw burned bodies strewn in the middle of the street. I will never forget that traumatic experience.

I left behind all my paintings, along with the tools and supplies I need to create art. I also have had to halt my dental training, putting my entire career on hold. My university, the hospitals and the clinics where I trained are all destroyed. There is no life left to return to.

My family and I were displaced two more times since then. Despite claims by the Israeli army that southern Gaza was a safe area, this was not true. Basic necessities were nearly impossible to find. Clean water was scarce, and aid from other countries was blocked by the Israeli army at the Rafah crossing, preventing it from reaching the general public.

But the most painful reality for me was that it was the longest period I had ever gone without drawing. I desperately needed to create, but I could not find art supplies. All I had at hand was a pen and some white paper. I urgently needed to draw to relieve my stress, so I settled for those. To my surprise, the resulting drawing is the most beautiful art I had ever created! But it is also the most painful.

It is a drawing of a woman’s face peering through a hole in the shape of Palestine, as if ripped in the paper, her eyes lifted to the heavens in agonised prayer. The woman is me. I titled it Searching for Home because, at that moment, what I yearned for most was home. And finding it felt like the most difficult, if not impossible, task.

In April 2024, I talked with my family about the possibility of leaving Gaza to resume what the war had forced me to pause. My family have always been my biggest supporters. They love my artwork and eagerly await each new creation. They were also thrilled about my graduation from the Faculty of Dentistry and looked forward to being my patients. Thus, they wholeheartedly supported my decision to leave Gaza to complete my dental training and continue my artistic pursuits, believing I could then fulfil my dream of bringing smiles to others.

You might wonder why we couldn’t all leave together. Leaving the Gaza Strip costs around £3,800 per person (to pay the ‘co-ordination fee’ required by the Egyptians to cross the border). To save my family of eight, the total would be £30,000. This is an unachievable amount given the circumstances of the war and the halt in economic activity. Leaving my family behind was the hardest decision I’ve ever faced.

So, I travelled to Egypt to save myself, while leaving my family behind in Gaza amid the ongoing war. I didn’t fully grasp the implications of this decision until I actually left, and my thoughts have been conflicted ever since. I am considered a survivor, but what does survival mean if I am not with my family? What is the value of surviving if it means leaving them behind? Should anyone have to make that kind of sacrifice? It seems that to learn and build a future, a Palestinian must give up a great deal.

Every day, I wake up feeling guilty. Was my decision the right one? When will the war end? Do I have the right to live a decent life while my family in Gaza endures such hardship? A Palestinian begins to question whether they have the right to a normal, ‘human’ life.

Nevertheless, I hold on to the hope that I can eventually bring my family here to join me. I’ve enrolled in a university and started to rebuild an artistic life. My painting, Searching for Home, travelled with me. Today marks three months in Cairo for me. I feel guilty and helpless every day. My communication with my family is very limited due to their weak internet connection. The lack of constant connection with them is difficult to bear. However, I remind myself that I travelled for their sake. My future is intertwined with theirs. I hope I can someday repay them for all they’ve done. Despite losing the paintings I spent ten years creating, I remain committed to my dream of opening my own gallery. I believe I still have a lifetime ahead of me to achieve my goals, and I will make it happen. This is the nature of the Palestinian people. We are accustomed to losing, but also to surviving.

Gaza, my homeland: it breaks my heart to see you in this state. You have always been the warm embrace that nurtured us, no matter the adversity. We love you in all your conditions – whether in peace or in war. We are committed to rebuilding you into a loving home once again. You deserve our loyalty, and we will remain steadfast. Your freedom is near, so do not fear.

Aya is now in Egypt and is exhibiting her art at galleries abroad. Her family remain in Gaza but have not yet been able to return to the north. When they finally do, they know that there is really no home to return to. Their house, like so many others, no longer exists. Her goal now is to reunite with her family in Cairo. But to bring them out of Gaza once the border opens, she needs a minimum of $10,000.