‘Cultural Amnesia’ Erased Black Women’s Contribution To Electronic Music – Now Artists Are Reclaiming The Genre

Black women are synonymous with electronic music in the UK – but in a tale that’s older than the genre itself, the layout of the industry would have us believe otherwise. It’s no secret that marketing, whitewashing and rebranding have seen artists who are typically white and male dominate the global mainstream of electronica.

In the US, listeners may be slowly cottoning onto the roots, informed in part by top-selling genre forays by big names (who could ignore Beyoncé’s Renaissance, for example). But many may not realise that Black musicians in the UK have been instrumental in contributing to the canon, notably in the ’90s and early ’00s golden days, when garage, UK funky, jungle and more proliferated the music scene via pirate radio and underground clubs.

Women were an instrumental part of the scene: see the popularity of jungle DJs Kemistry and DJ Flight in the 1990s, at a time when house veteran DJ Paulette became the first resident woman to spin at the legendary Hacienda, and singers such as Rachel Wallace, Sonique, Kele Le Roc and Nay Nay lent vocals that turned underground productions into mainstream successes. Then there are the MCs: Ms Dynamite, Lisa Maffia and MC Chickaboo, who all held their own among male-dominated line-ups in the ’00s.

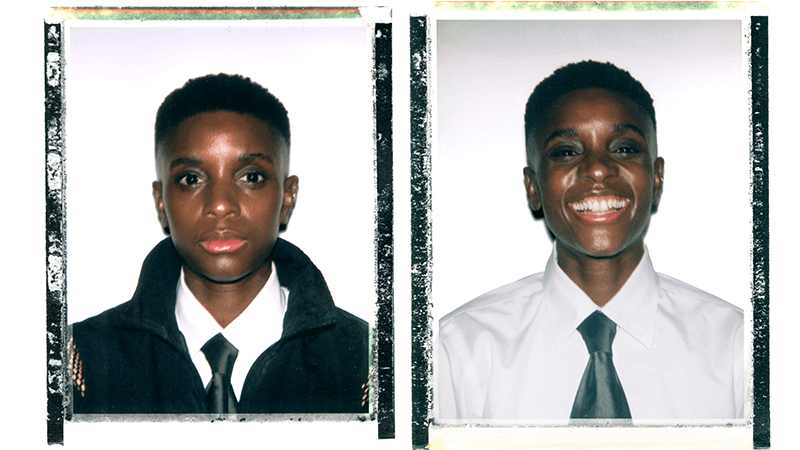

Garage is a genre that would become well known to DJ and vocalist Eliza Rose, who took 2022 by storm with her hit B.O.T.A. (Baddest Of Them All), a song that made her the first woman DJ to hit No.1 in the UK since Sonique in 2000. Rose, who is of Jamaican heritage, had been drawn to electronic music through time spent in record shops growing up but wasn’t initially aware of its cultural origins.

“When I first started DJing, I saw playing electronic music as a kind of white male thing,” she says. “The people at the head of that were men, and there wasn’t much space being created for Black women.” It was only when she reached her early twenties in the 2010s that she discovered some of the Black women who’d shaped electronic music culture; the likes of Manchester’s DJ Paulette, and other trailblazing selectors including Marcia Carr. Her experience speaks to a wider cultural amnesia that leads to challenges for Black women artists and DJs – facing box-ticking listings on lineups (if present at all), while white or male counterparts often command more celebrated bookings.

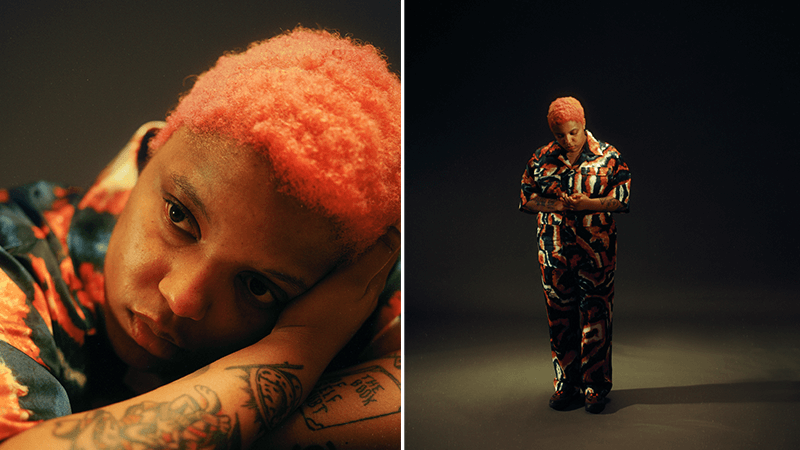

Loraine James is a musician blending multiple electronic genres, often experimental and uncategorisable. Even after working with electronic giant label Hyperdub and years spent touring internationally, she’s experienced slights that seem subtle, but speak volumes. “Sometimes I see a difference in the way I’m spoken to compared with my white or male peers,” she says. “I’ve felt if I’m asking for something to be changed, like in a soundcheck, for example, a few sound technicians have been pretty dismissive, like they don’t want to do their job.”

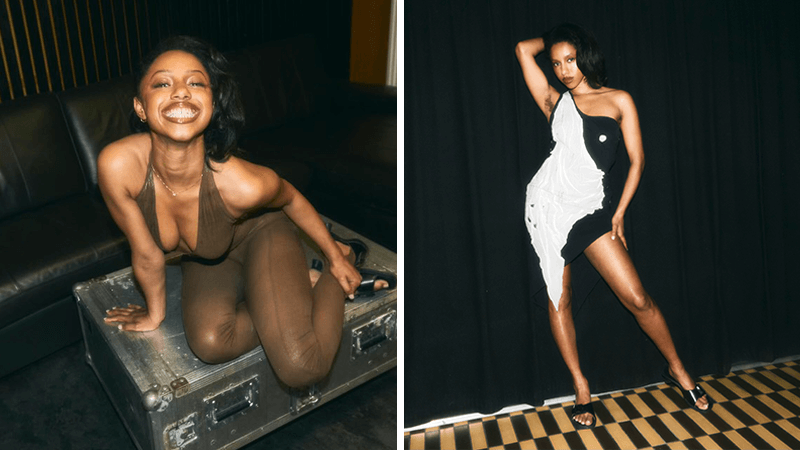

Having one’s genre of choice perceived as ubiquitously white distorts perceptions of Black women who want to make music on their own terms. George Riley has become known for soulful, R&B-leaning vocal runs and melodies over the most far-reaching of electronic production; working with the likes of Hudson Mohawke, Actress, Anz and more, and even travelling to the home of techno, Detroit, to compose her Un/limited Love EP. But she feels Black women are often treated as novices in music we’re at the origins of. “A lot of the ‘white man producer’ archetypes that you meet along the way are quite copy-and-paste in the sense of entitlement,” Riley says. “Even though they might make different music, that ‘I’m light years ahead of you’ attitude exists – thinking they know everything and that you’re an idiot. You have to be on your own path so much.”

Black women’s experiences in electronica are doubly affected by wider societal issues: namely racism, sexism, hyper-sexualisation and more. Riley has found that those in power often grant valuable resources – even simple time and support – in the hope that things will go in inappropriate directions. “Lots of the producers... sometimes it can be a prerequisite that if they fancy you, they want to work with you,” she says. “That is obviously upsetting. And to what extent does one feel like you have to participate, or even be present, when that dynamic is happening?”

Despite these problems behind the scenes, Black women artists are achieving more mainstream cut-through. Post-summer 2020, event programmers and industry heads are eager to give an appearance of equality, so we’re seeing further diversity on lineups, community initiatives, incubators and more. Plus, there are Black British artists who are taking electronic music styles to the global level; key figures such as PinkPantheress, Nia Archives and Shygirl, who through club and Eurotrance have amassed MOBO wins and Mercury Prize nominations.

But these examples raise another concern of who is given license to cut through. All these artists are of mixed heritage or lighter-skinned, an issue of colourism the artists I discuss with all acknowledge. The question of which type of Black women can be considered successful plays its part in social media and digital hierarchies, suggesting time and time again that – bar a few examples – being of lighter skin is essential to success.

Still, there are activists working to address these imbalances. SHERELLE is a heralded DJ and producer who has launched community incubators such as BEAUTIFUL, as well as this year’s London-based exhibition Move/003, which traced the Black and LGBTQIA+ history of UK electronic musicianship. And organisations such as Black Artist Database and Club BEMA have also made moves to strengthen the positioning of Black electronic artists in the industry at large.

But, as always, there’s still a long way to go to make electronic music a safe and inclusive space for Black women. “I want to see people doing their research and getting the correct person for the lineup – I don’t want to see that tokenism,” Rose says. “Also giving Black women better slots, not just warm-up slots!” And above all, progress must start from one thing – remembering that Black women of all types have always been at the heart of electronica.

3 Electronic Mixes By Black British Artists To Discover

7 Classic Electronic Tracks By Black British Artists To Enjoy

Christine Ochefu is a London-based freelance writer and copywriter covering music, arts and culture for titles including W Magazine, The Guardian, DAZED and i-D Magazine. She is currently working on her first novel

Get the best of Service95

delivered straight to your inbox

By subscribing to our newsletter(s) you agree to our privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.